Books and Beyond with Bound

Welcome to India’s No. 1 book podcast where Tara Khandelwal and Michelle D’costa uncover the stories behind some of the best-written books of our time. Find out what drives India’s finest authors: from personal experiences to jugaad research methods, and insecurities to publishing journeys. And how these books shape our lives and worldview today.

Tune in every Wednesday!

Created by Bound, a storytelling company that helps you grow through stories. Get in touch with us at connect@boundindia.com.

Books and Beyond with Bound

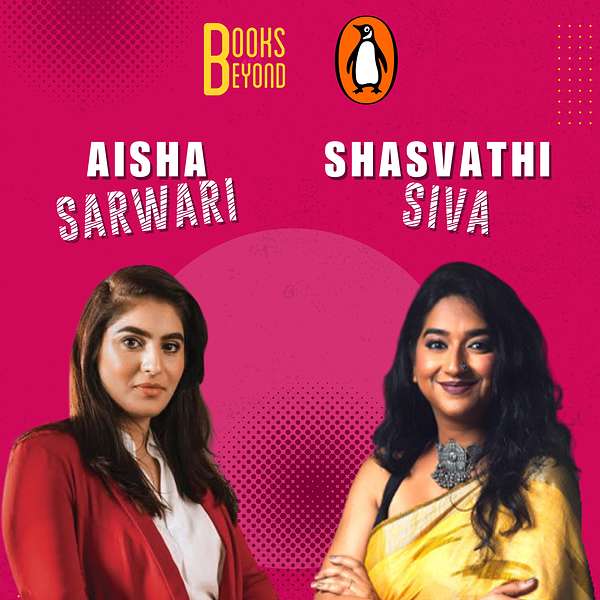

6.12 Aisha and Shasvathi: The Real Reason Behind South Asia's <1% Divorce Rate

South Asia boasts a less than 1% divorce rate. But the real reason behind it is far from happy marriages.

In this episode, Tara and Michelle sit down with Aisha Sarwari and Shasvathi Siva, as they talk about misogyny and marriages in South Asia.

Aisha's book, 'Heart Tantrums', is a memoir that addresses her immigrant life and her marriage to a man with a personality-altering brain tumor and how, despite the grief and abuse she faced, she was told that being a devoted wife would fix everything.

Shasvathi's book, 'Divorce is Normal', is a handy guidebook that aims to normalize divorce and provide legal, emotional, and mental support for anyone going through divorce, or considering it. What is it like to be a divorced woman in South Asia and why is there so much stigma attached?

In this exclusive series in partnership with Penguin Random House India, we will shine a spotlight on two compelling contemporary voices each month, individuals who are reshaping the landscape of Indian literature.

Join us in a thought-provoking conversation as we delve into the realities of South Asian marriages, societal expectations, and why it's always better to "struggle with the community"!

Books and authors mentioned in this episode:

When I Hit You - Meena Kandasamy

Rewriting My Happily Ever After - Ranjani Rao

How Much is Too Much? - Neha Mehrotra

The Handmaid’s Tale - Margaret Atwood

All About Love - Bell Hooks

‘Books and Beyond with Bound’ is the podcast where Tara Khandelwal and Michelle D’costa uncover how their books reflect the realities of our lives and society today. Find out what drives India’s finest authors: from personal experiences to jugaad research methods, insecurities to publishing journeys. Created by Bound, a storytelling company that helps you grow through stories. Follow us @boundindia on all social media platforms.

SPEAKERS

Tara Khandelwal, Aisha Sarwari, Michelle D'costa, Shasvathi Siva

Hi, everyone. Welcome back. So Tara and I have covered really different kinds of narratives about women on this podcast before and this women's month. We are very glad to speak to two really talented female authors, Aisha survery, and chastity Sivan who are the authors of heart tantrums and divorces normal. Now they are going to unpack for us what it is like for women to be married or divorced in South Asia. So listeners, please exercise caution because this topic could be distressing for some as it involves abuse and violence towards women.

Tara Khandelwal 01:05

Yeah, and you know, it was really funny because I was reading both the books and I recently got married. So the divorce novel book is lying around. And my husband has a vote are you doing so the timing could not have been more ironical? But you know, these books are really so important. Michelle and I were discussing, just sort of, like, capturing what it was what it's like to be a woman in South Asia. And, you know, in your book, crashworthy, it says that India boasts of a divorce rate of around 1%, without much thought for what it actually means, right? Because how many married couples are actually happy? And how many married couples do we know that are stuck in marriages that are unhappy, and it's really heartwarming to see that the stigma around divorce is decreasing, though there's a long way to go. So shashlik work is starts when she decides to end her marriage. And she realizes exactly how difficult getting a divorce is in Indian society and legal system. And in the book takes us through, you know, what to do when you're getting divorce, what you know, if you know, someone who's getting knows how to sort of talk to them, the stigma around it support groups, lawyers, therapists, and the whole gamut?

Michelle D'costa 02:29

Yeah, and totally, you know, I have the opposite experience. As a single woman, you know, when I read these books, I was like, Whoa, they're like, cautionary tales, you know, for me, so I chose this book, you know, on the other hand, it sort of, you know, navigates her life, you know, from her childhood to sort of the stage She's in right now, you know, when she left her family home in East Africa, she had to fit in a completely different culture in Lahore, you know, after marriage, you know, and she slowly began to lose her husband to a personality altering brain tumor, which is some of the most challenging scenes in the book and quite difficult to read. A, you know, a book is really searing. It's sort of a searing look into intimacy now, Marriage Divorce, what not? So let's speak to both of these really targeted women who have written these brave memoirs that make us really look, marriage and divorce in South Asia. Welcome.

Shasvathi Siva 03:23

Hi, thank you so much, Michelle. And Tara, I think I just like, one thing I just want to start off with, right, which is exactly. Tara, you gave me a great in to, like, actually introduce the book as what you said that you just got married. And then you know, like, this book was lying around, do I know the title and the cover of the book and make it look like it's a thing, but I truly believe that, you know, where the concept and conversation about marriage exists, the conversation about divorce has to exist. And I'm not I don't mean this in a cynical way that you know, if you're in a happy marriage, or whatever, you need to be thinking of like, Oh, what are we separate? What if we do this, but I think it's more about arming yourself with the information, especially as women especially living in societies, as you know, so with such deeply ingrained stigma and the kind of, you know, just to even understand what rights you have what you need to do, because you need to understand it, right? It's a part of marriage, it's ultimately it becomes a transaction at some point of time and you are involving the government and it becomes like a legal thing for you to sort of get into so I think while yes, it's it's weird for that book to lie around when you're immediately married. However, I think the conversation doesn't go out of the picture. I think it's a conversation and I truly believe that your partner and you should be comfortable enough to even discuss it to say, okay, you know what, just be practical about it tomorrow. Things do not work out between us. What do we do? You know how you want to go about it. Of course, this is keeping in mind that, you know, nobody harmed the other person, nobody cheats on the other person, all those things kept aside. So that's just something I wanted to say when you said that thing that that industry is. And I think the book I have written also is not only for people going through a divorce, and this is something I've kind of said repeatedly on like multiple platforms, I'll continue to say so because I think it's a book that's written for many people. And I think that, especially for those who are looking to get married, or have been like newly married or on the verge of like getting engaged or thinking about this big decision, etc, then I think it's more important for you to be aware of, and that's exactly when Michelle also said that, you know, as a single woman, it's almost like a cautionary tale, but then you kind of understand what other people have gone through what do you look forward to you? How do you prepare yourself. So it's coming from a very practical lens, of course, and keeping the emotions a little bit aside to see that, but you need to be practical to protect yourself to safeguard yourself, God forbid you do it in the in the future, actually,

Tara Khandelwal 06:03

you know, we are bang on because right before I was getting married, I was having cold feet, and I was discussing with my husband, and we were like, You know what, at the end of the day, it only feels so overwhelming. When you feel there's no way out. And the minute that you feel like okay, you know, if things really go really down the drain and everything this is not like that as permanent as you're thinking. And I totally agree with you in which you know, it needs to also like be brought into the conversation in a practical manner. So definitely, 100%

Michelle D'costa 06:38

Yeah, and, and so, you know, I think, you know, adding on to that, Aisha, you know, before we go into, you know, deeper into the book, and sort of you know why you wrote it and all of that, you know, we would love to know more about you because we read that, you know, you were born in Uganda, in a country family, actually, and you were educated in America, you know, then you settled in Pakistan post marriage. So there's a lot of movement in your life, right, I'm imagining the culture shock would have been great. You know, and you've done so much in your life, you've written a lot of articles for a lot of platforms, you know, regarding feminism, manage divorce, all of that, right. And you've also co founded a women's advancement hub, right, which actually works for the welfare of women in Pakistan. So we would love to know more about your background, sort of, like, you know, how did that influence the book a little more about you?

Aisha Sarwari 07:28

Thank you so much. First of all, let me just say that absolutely love your podcast, I was taking a look and ended up listening to I think six today back to back. So amazing page turners, if I may say, and the podcast, whatever that is. So about me, I think that you picked up on the right theme, which is migration. So in our life, it's just been one movement after the other. Whether it is my Nana and nanny who moved from content, before partition to East Africa, you know, this was the real good migration people. Or it was my dad's side of the family that were almost plotted from Edgemere, and then sort of flushed out into Karachi and Hyderabad. Or if it was my dad moving from Karachi, to East Africa, because he just did not agree with the new dynamics in the family in Karachi. Or if it was my mom moving from Kenya, which is her home to Uganda. And then obviously, my life is from Uganda, to Kenya after my dad died. And then from Kenya to the US, too, but back to Lahore, and then between the horizontal interaction. Now, that is a mouthful. And the reason I'm telling you this is because migration leaves a certain amount of displacement, a sense of loss and sense of dispossession in a person. And that is now we know, to generational trauma passed on from person to person to person over generations to and it's mostly absorbed by the women. Were there absolutely more actually of using them?

Michelle D'costa 09:05

Yeah, so sorry, I should put you Yeah, just the voice is a bit muffled. Maybe, maybe if you if you sit back, probably it might. It might be clearer. I think this is

Aisha Sarwari 09:17

clear. Yes. Okay.

Michelle D'costa 09:21

It was anything in between? Right? Yeah. No, I told ya before you like, you know, like finish the entire answer. I thought it's better. We could like, you know, you can continue, like where you stopped?

Aisha Sarwari 09:31

Yeah. Okay. So as I was saying, I think that the biggest fear is absorbed by the women in the family, who then have to pack up and leave at every whim. So there's no sense of rootedness. There is no sense of ancestry, you know that my great grandmother is buried here. Or this is where, you know, I had like my family home. There's a sense of nomadic pneus which has also seeped into my life where I'm often I struggled to find All right. And in that struggle, the fear of losing your home has been has been greatly overstressed in my life. So when you say, you know, these books are a cautionary tale they really are because on one hand, it is someone like me who's been so afraid to leave the marriage no matter what the situation, even if it's traumatic brain injury on the other side of your spouse. But no matter how bad things get this fear of losing your bearing, or your home, you know, already because people can become your home, right? So that fear is so palpable in me that no matter how cognitively evolved, I've got no matter how much I know cerebrally what's the right thing to do. And what's the feminism on this? That from a somatic perspective, I just haven't been able to break a lot of those barriers and I would rather do anything then be sort of dispossessed if that makes any sense.

Michelle D'costa 11:03

Right, I think we're I think there is a there's some internet issue. Just give me one second.

Shasvathi Siva 11:17

Think it was fine for me, I could your entire answer.

Tara Khandelwal 11:23

Yeah, just check.

Aisha Sarwari 11:28

On my mobile data as well, just in case the Wi Fi isn't strong enough. Give me a moment

Shasvathi Siva 11:49

okay, while they figure, I'm really loving your book. I'm really liking it. I read your thoughts three. Oh, thank you. Okay. Yeah, I

Aisha Sarwari 11:57

really didn't pay attention. So I'm a little slower, but it's so funny and familiar that we could have been the other one, like I could have left and talked about it. And you could have stayed and talked about it like that the ability of the similarity is amazing. Yeah,

Shasvathi Siva 12:16

sometimes I was just turning the page. I'm like Vashi not leaving machine or leaving.

Aisha Sarwari 12:22

I'm not leaving because when I'm reading yours, it's like, I'm glad you know, I didn't I'm glad like this is what I knew was on the other side. You know, the legal battle the humiliation the victim blaming.

Shasvathi Siva 12:34

Yeah, so I don't know how your book is ending. So I don't want to know what what happens from there. So I'm, I was I was extra my best to finish it before the podcast, obviously, because before meeting you, but since the books been so hectic, I manage like 1015 pages a day, and it's not been enough to finish unfortunately,

Aisha Sarwari 12:55

you guys are avid readers reading is not the culture here. Unfortunately, like you just don't see it regardless, even in the educated people rather like throw money at art and go to vacation rather than sit and be they're not, you know? Colonia? Hey, what are you doing? What are you doing these days?

Shasvathi Siva 13:22

I woke it up in advertising. I work as creative director. So you know that that's most of my most of my day and some of my nights also. Okay.

Aisha Sarwari 13:33

I'm also in a similar field. I'm the Senior Director for Public Affairs, communications sustainability at Coca

Shasvathi Siva 13:39

Cola. So it's just so cool. Yeah,

Aisha Sarwari 13:43

yeah, it's got its own sort of, you know, expansive, work, but most of it is creative work. So that's where I started.

Shasvathi Siva 13:53

That's amazing. A lot more to talk about that. But maybe

Michelle D'costa 13:59

I love the wrapping. No, I'm

Aisha Sarwari 14:00

sorry. I'm sorry. I didn't realize we will be better waiting on our site. But we're waiting for you to turn.

Michelle D'costa 14:06

No, no, I think there was some there was some internet issue at my end, but it's been sorted. Now. I restarted my Wi Fi. Okay, cool. All right. So yeah, now that you know, now that we know you know about Aisha is god of it. Chastity. katoa. Tara, do you want to go you can ask for extra kick. Okay. So now that we know, you know, a bit of what eyesize journey chastity we know that you know, you were born and raised in Chennai, and that you grew up in Bombay, you know, and you're again, you know, just like Aisha, you've also been a prolific writer, you know, your publications have been a lot of journals like Vogue, India, the Quint, and all of that. And I also saw one of your TED talks, which is really cool. It's called to live do as a part, I think that's quite popular. Right. So please tell us a bit about your background and sort of how that influenced your book.

Shasvathi Siva 14:53

Um, so yeah, I did. I was born and raised in Chennai for a good part of my childhood and that's one of the Oh, best things I could have gotten super grateful for that. Love Chennai. I have been in Bombay and I think I continue to grow up in Bombay. And I hope that never, they will stops, I don't ever want to say I'm fully grown up, I want to continue growing up. I think when I was getting divorced, I think it sort of changed my life, right. So when you're talking about like, what sort of led up to the book, it's actually a very weird journey, almost because Byler getting divorced, I felt like the weakest person possible, I don't think I even thought for a second that there will be a time where I'm invited for like, talks. And then there are like these, there's a whole book deal, and there's so much coming along with it, it was, if someone had told me this, at that point in time, I would have just laughed them off a little bit. Like, there's just no way that I can even think of it. Because I also think like when you're standing in court, and when you're going through, like all of these things, there's the very few things you hold on to that actually make you feel, you know, strong. And I think one of the things that I always had was hope. And that's something you know, I've tried to talk about and a lot of things also to say that, you know, like, one bad experience isn't going to put me off everything. So I was like, going through this divorce doesn't mean that I'm not going to find love, or I'm not going to like, you know, find what I want. And I did want companionship live. It's not, it's I wasn't like, oh, I want to be single for the rest of my life. So I think because I had that in my head, on some level, I held on to that hope. And I think you need to hold on to something when you're going through all of these things, right? All of these things at once I sort of just like, it's bogging you down to an extent and then you just want to say, okay, you know, where do I go from here? I think that also gives you something to like, look forward to to say, okay, you know what, let's put all this behind me. And then I have something, something new, something refreshing. So I think I would often think of that, like, it will be a little Daydream me, but then you know, I needed I needed that. And I think when I saw people around me sitting in court, it really bothered me, like, you know, the fact that so many people who would just be like people crying in the corners of the court, they'd be like, children, there'll be like, screaming matches. I mean, it's it's there are so many emotions that are going on, because every case is different. And imagine 50 cases coming together on a daily basis, over there. So there are that many different sorts of emotions going around the waiting room, and I'm talking about DKC, Mumbai, High Court, Mumbai family court, sorry. So over there, and I just realized that, you know, we are all pretty much going through the same thing, maybe not exactly the same thing, but somewhat the same thing in different you know, wordings on different pay legal papers, and all of that, but ultimately, some there something that we are all going through in this particular building and floor right now is like so similar. And why don't we have something that you know, that we can actually help each other. So I think the idea of forming a support group for me, came very early on, and one of the first times that I went to when to coat in itself, I was just like, you know, what, we really need a space where we can all sort of like come together, because there's nothing like shared lived experiences sitting and talking about or to the other person, I think there's that familiarity and that comfort that you cannot get with. And you can have the most, you know, wonderful friends and family around most valid tension, all of those things. But when you speak to somebody who's going through that, or has gone through the feeling, and the understanding is you know, you just just feel like, you've been misunderstood for a long time. And someone's finally getting what you're saying, you know, that kind of thing. And I really wanted to have that. And I was looking for it myself to say like, there anything in India, there's something online instead. And I was really fun when I wasn't finding anything. So I said, you know, after my divorce ends, and after I put all of this shit behind me, I need to like sort of, if it's not there, then I will create it because they're clearly fine feeling and I'm sure other people have felt it. So there is there is demand that somebody needs to, you know, plug that gap and say, Here it is. So, so that's what I did. And then I think once I set up that support group, and we had the first initial few meetings, like you know, I would talk to restaurant owners who would allow us to open who would allow us to sit them before they open. So if they were opening at 11 for like lunch, I get the space from like, you know, eight to 10. So, without disturbing their business in any way. I spoke to some yoga to do so. Somebody's tariffs. So all of these things were where we were meeting. And the more I met people, the more I was convinced that we need this to be, you know, like on a bigger platform, etc. And then the pandemic happened. So it took on, like, an online format, which was great, because now it was like, you know, global liquidity wanted, could like sort of, like, join in and you know, you could have these conversations. So I think it was, it's just started like that. And then, before I knew it, it just became I started talking about it only online, I think I just wanted to use my voice there. And I mean, it's just, I'm just, I just feel very lucky that what I was trying to say the message I was trying to communicate and put across just got bigger platforms and better platforms to actually put that right, because now there's a book that like, like you said, that there are these talks. So I think it's very important. And I think that, you know, I will always keep talking about it. I don't think I would ever until that, that stigma is completely gone, which might not even happen in my lifetime. But it's something that you know, I feel so strongly about that. No, I don't want a single person to feel isolated, I don't want a single person to feel like they cannot do this. It's exactly it's a, it's a choice, as much as you make a choice to get married, if you should have that freedom of choice to get out of it. Also, I think just that passion, of that, taking that message forward, along with my own experience. And, you know, the fact that I was able to set up that support group, and even now it's running, it's on on telegram we have about between 607 100 active participants who every day the group is active every day there are people joining. So I think I strongly believe in community, I strongly believe in people coming together. So yeah, that's pretty much what brought me here. It was not to say, you know, when I turned 20, I wanted to become an author. It wasn't that everything that's happened has been sort of platforms for me to take this message forward. And tomorrow, if there's another platform, and if I have an opportunity, I'm more than happy to do

Michelle D'costa 22:10

it over there. Yeah, totally. No, I think more than the the app, like I think your passion clearly comes across, you know, just within whatever you do, even in your book. But I do want to touch upon this aspect of support system that you mentioned, especially because I have a story to share your so one of my Auntie's who's like I'm very, pretty close to her, she went through a divorce like a few years back. And it was a very difficult phase in her life where she didn't, you know, when she cut out people, she didn't want to share things. And the saddest part was that it was a love marriage, it was sort of like, we really looked up to that couple, to sort of say that they are the ideal couple, and then things just went haywire. But what I really want to focus on here is that she's outside India, so she's in Canada. And what she mentioned was is that they have such a strong support system for people who are going to anything might be in their relationships, you know, where the system is sort of set up in a place where you're given support. And I remember what she said is that if this I had gone through the same thing in India, I don't think I would have got this kind of understanding, be it in the workplace, be it in, you know, anywhere else where you expect that system. So I think that's something that stayed with me and, and when I read your book, chastity, I really, it's sort of like, you know, hit the nail on the head. And I realized why it's so important to have these kinds of support groups. It's also

Shasvathi Siva 23:21

it's very important, because in India, we also I had written about this in my book, also, we do not have no fault divorces, which means that if two people are in a marriage, and they just want to get out of it, because they just don't want to be in that marriage, you don't have that choice, you have to put the blame on the other person, you have to find a fault. Which means that as a country, we believe that unless something is so wrong, you can't get out of a marriage. And that's exactly what I'm also challenging and fighting to say you can't fake that. Of course, it's the law, but it's gonna be a long time. But that's the reason. places like Canada or even my cousin who got divorced in the US, literally, it got done over an email because it was mutual. And all of those things. I didn't even have to go to a court to do. Right, right. It's very different. That's never going to happen, you know, the processes are very different. So I think the fact that we don't have no fault divorces in our country itself shows that we are not open to accepting divorce. So then where is the support? Right? Where then where does it come? So you need to find your own circles or circles like this where other people are sort of doing it because most families only don't support it. Most parents are still not supportive. I have people even in my own circle, you know, whose parents might have a lot of opinions about other things, but when it comes to their own children, and when it comes to their own children wanting to come back home or her getting a divorce, the court system? Absolutely. Yeah, I

Michelle D'costa 24:49

think yeah, no, no, I think you're right. So so like now it's sort of it's very interesting, because now I'm thinking of okay, what the system is abroad, and as you mentioned, what's in India but what's interesting in Africa He says Asha, you have encountered this in Pakistan. Right? And and you know, you've had a lot of ups and downs in your marriage to your husband. Yes, sir. You know, and and you've shared how, you know, sort of he went through this, you know, sort of personality altering brain tumor where there was sort of two sides of him two versions of him that you've encountered, right? You know, and in fact, one, one of both sort of a version where you call him a selfless driven historian and lawyer, you know, who would be invited to be, you know, a fellow at Asia Society, or Harvard Law School. And on the other hand, you know, you would sort of be a be, you know, you will encounter a juvenile who have a lack of self awareness, right, two very different people, but you've had to encounter them, and you would never know which version would meet you on a particular day, right? I can only imagine how harrowing or how confusing this must have been for you. You even in fact, maintained a journal where you documented all the difficult times that sort of came up. So I want to understand sort of how do you, you know, sort of encountered this particular phase? You know, how did you sort of understand, which is this version of him, which is the tumor speaking and which is him?

Aisha Sarwari 26:13

Question, Michelle, because a lot of people, you know, how she does what he said that you talk to people who have been divorced, and they get it instantly, they get the pain, they get the anguish. So a lot of people who are the caregivers are the primary caregivers of somebody with traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, dementia, autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, any of those things that have to do with something that appropriates the brain's key functions such as empathy. The moment I explained my story to them, they get it, there's nothing, they don't even get surprised. They're like, Oh, you know, okay, yeah, whatever. Yeah, that's how it is, yeah, you get things thrown at you sometimes. Or sometimes, when they're in the hospital, or they're in a lot of distress, they will accuse you of trying to, you know, poison them. So so the paranoia, all of those things are superbly normal in a in that context. And so, I actually found a lot of solace in those support groups online that, you know, had the care perspective or given care to somebody who's really not there anymore, and yet, you're holding on to who they really are. And there's this big friction and tussle between the fact that they're struggling with mental health, and they have a dignity and the right to their dignity and the right to their core, which is on touched and pure. And at the same time, you as a victim and as a carer of the of their behavior, which may not have been intended to hurt you, but is hurting you very directly and very squarely. And what I the reason I sort of came out to speak with my story was because of the hypocritical society, both in India and Pakistan, remember, I have half India in me and half autonomy and a bit of America and a bit of Africa. So you, so there's no excuse that I could have found my strength any in any of these communities. And yet I did not. There was a universe so good that you're going to your husband's house, you've chosen him. And that was the other added pressure that I had, that it was something I had chosen consciously, not because it was an arranged match. So now that you've made this choice, do not return without a successful stamp of, you know, sealed, signed and delivered. Either you die or he dies, you know that that's the sort of metal you're going to get at the end without fully understanding what that means. So I think initially, Michelle, you said, you know, there's a 1% divorce rate and everybody in India superbly proud of it. And it reminded me of this wonderful author that we have in Pakistan for her name is Mr. Xi. She's obviously deceased now. But there's a story that she wrote, and she was a very risky writer. And this is a short story she wrote in which somebody in the neighborhood has her husband die, and so she goes to the funeral. And so all the women are making this dis widow take off her Carta, her jewelry, her tomb cause making her wear white or black and telling her your life is over. And she was very, very young. So it's not just I goes and she makes aware her girls and her ganas and her jewelry, and she says, your life just started today. So today is your first day of freedom. So there's this alternate view, which does not necessarily celebrate the 99% of people who should be in the 1%. But you really said that, you know, it's not what it seems like. There is a certain oppression that's happening in these societies, where you're using silence as as a trump card or as some kind of trophy but that's not something to be celebrated. What what silence is doing is it's making the sons of those models who are silenced by the cartels, or who are oppressed by the father's pocket on to their wives. And in most cases, wherever there is violence some severe aggression, it has been passed down as, as learned behavior. Because either you recognize that your mom was a loser for not speaking up, or you recognize that your wife, therefore, is too out of hand. So there's so much of, again, that tension between, you know, either, you know, a human being is not capable of learning things too quickly over a lifetime. So they have one life and in that one life, they just, they just have one mother. And in that one life, they have one wife, and they don't have seven, right? So it's not like they're going to iterate or learn like AI, they are learning impaired. So their lived experience is going to pass on constantly to other people, if they were bullied, they will be bullied, you know, it will take them a couple of deaths to not play, right, you don't just stop Chroma where it starts. So I think that the status thing that the subcontinent has given to our women, and particularly everywhere in the world, as well, is not an exit clause that is dignified. Even when you're buying a rental property, you should look at the exit clause. And what if this doesn't work? What if the termites in the house, right, you still get a bit of an out, but in the case of a marriage for women, particularly there is no way back, and that is celebrated. So a lot of people come to me and they're like, We admire your honesty. And, and this is what got me to sort of come out, right, because I was getting so many accolades. If there was anyone else, they wouldn't have stayed. You've sacrificed so much, you're such an honorable woman. And what a wonderful wife, what a perfect wife for sticking it out. And, you know, despite the fact that it's been such a long winded journey of mental health, with chemo and radiotherapy, and two surgeries and the chaos, and you know, raising two girls, you did such a good job. And I was a bit, I didn't know what to say to that. Because a it wasn't true. I didn't have courage, I had broken down completely. And I had failed miserably. And it was building this pressure on me to be good. And there is no way you can be good in such a situation, right? This is chaos. It needs a community for everybody to come together and heal this person who has a mental health challenge. And yet, the entire industry of marriage puts that caregiving duty and that nursing duty on the woman and on the wife, and it breaks her back. And so I wanted to just say I have failed. This is how colossally I have failed. And I do not like it was a rejection of everything that the institution of marriage stands for. Because I was all alone. There was no community, there was no support system. I was blamed, I was constantly chastised, I was sort of judged for what I was trying to do the best that I can. And even though people knew that there was a certain victimhood to what I was experiencing, people either looked away, or this or they couldn't graduated me for being a good, honorable wife, which was I think, horrendously untrue, you know?

Tara Khandelwal 33:11

Yeah. And I think you all of those complicated emotions come out in a memoir. So well, parts of it were very difficult to read, because it's just so honest, and so visceral. And you really just sort of read it all. You know, I'm sure that wasn't easy at all to do. And I think the very first thing that, you know, made us want to read further, because we obviously you did a bit of research, but what the book is about, and your journey is the foreword, which is quite unexpected, because it's actually written by a husband, yeah, acid, where he takes accountability. And, you know, he expresses his regret for the way that he might have sometimes treated you because of the illness. So what was it like having him write this forward? And why that decision? And how do you think that it impacts the reading experience, visa vie the rest of the book,

Aisha Sarwari 34:10

thank you for seeing what you said. And thank you for picking up on the word. See, had I been reading this book alone without your schoolwork, and without his utter honesty, nobody would be able to see the person that I was still sticking around for. Right? It would just be some version in my head and I wouldn't be able to give a glimpse of that to the world. Where to the point that he also has actually honestly said in his foreword, you know what I it could have been the brain tumor, which was five centimeters big. And there was very good physical and scientific and legal evidence that I could not be held responsible or accountable for anything that happened during the DOS days, which is a 20 year tumor, slow growing. However, he says that there's also a doubt that I have that this isn't pure luck. Such a thing that made me like lash out at I shared the first soft object that I got. And I think that that sort of like moment where he was my old Yasser because I knew him since he was 20. And you know, I knew him before the tumor. So it's like I'm holding on to I'm the only witness maybe him, his mom and me, probably the only two witnesses, maybe some friends who knew him before the disease took him from us, right. And so, now I have two people, and I wait for the other guy. So obviously, this COVID was written by the, by the guy that the world honors as a human rights lawyer that the world was packed. That, you know, knows, he's the biographer of our founding father, and the person who granted me all that freedom that I thought, because remember, patriarchy worked until it didn't. Yasser did give me the protection from a really terrible society that others other men didn't give me, but he gave me. So it worked until suddenly he fell ill and it wasn't there, which is really a big lesson for all of us women that let's not rely on men to be kind, let's rely on institutions and laws, because anything can change, they can get a tumor, they can change their mind, somebody can whisper in their ear. And by the way, I brought this up, because I feel like all South Asian men have tumors of some kind. You know, there is some kind of brain deadness Where did you just do not exercise. They don't check their privilege. They don't understand how it is for women's lives. And they're just very arrogant in their, in the way that they conduct themselves. They have no sensitivity for how hard it is to be available to speech. And so which is why I wrote it, because I got my Get Out of Jail Free card for Yassa. And then he also validated what I was writing, and sort of, you know, he could have called me a liar. He could have said, you know, I don't stand by this, which sometimes when he's on the other side of the personality shift he does. But thank God that I had one little portal of truth where I could get this in writing. And I could remind myself and the world and his daughter's that this is who he truly was, you know?

Michelle D'costa 37:12

Yeah, totally. I think I think for me, that was the sort of the impetus for reading the book. In fact, like one of the most interesting four words that I've come across, you know, because I think in memoirs, what also happens is more like, it's your take on the story, but your there was a flip side where you could see his take as well. You know, and I was telling this to Tara the other day that, you know, if we place both of your books on the bookshelf, they would really stand out from each other, especially because of the size, you know, where Ayesha's book is almost the storm, you know, from where, you know, you're sort of you're, you've not left any stone unturned, right, you've covered a lot in your book, Aisha, whereas on the other hand, just with your book is, is really focused really slim. And it's sort of more more of like a handbook, you know, for those who are going through this process, right, and you haven't really shared much of your own divorce or sort of your own relationship. And you've even mentioned why you said that you didn't want to go into the past and sort of relive the memories. So could you please talk us through this decision that you came up with, you know, especially not to include your own stories.

Shasvathi Siva 38:15

Um, the first thing, I mean, a great observation. But time is also obviously, you know, I think I, it was a very intentional decision. And also not just the size of it, but even the writing style that I took was a little more easy, you know, it, I did not want to make it feel like a very heavy read, I didn't want to add to the problems because especially And this I say, keeping in mind, people going through a divorce. So it's already difficult, you're already exposed to so much of like, things with your loyals and coats and people's and emotions and emails and all of those things. So in the middle of all of this is that if somebody has to recommend this book, to this person to say, hey, you know what this might actually help you, then I wanted the book to actually be of help, you know, if I if I went too much in detail, or made it a very, what you say, loaded it with a lot more emotion or made it very heavy or a longer read. I feel like it wouldn't have served the purpose of what I was trying to do. And I think the purpose of the book also to a large extent, I kept it very, very, very particular that it's, it's it brings a lot of shared experiences together. It's not just about me or what I went through or what either it's about seeing that every person goes through it differently though, via probably going through the same process. The way we see or experience or react to a few things might be completely different and I'm about to say that the divorces are of so many different kinds to talk about. Children will have, you don't parents who are divorced to talk about, you know, people who've gone through a divorce when they were very young, very old, sort of my, my intention was to get more of these stories, because I don't think it's an uncommon thing to go through a divorce, the more important part of it was to say that, hey, it's happening all over you, that just said it's happening. Whatever is happening is happening very quietly, people aren't allowed or encouraged to talk about it, like you know, something to be proud of her even something to be happy about, like you never know, a divorce could make somebody extremely happy, because they finally out of a relationship that they do not want to be in. But people around don't want you to sort of like celebrate it. So I think that's what I wanted the book to, like, sort of do be this kind of a light read, like, you know, you get on a flight, and you're probably done at the end of it kind of thing where then then it becomes easy to digest and consume this content that's been put in front of you. So I think that was an intentional decision that I made. As far as why my one study, I just think it's exactly what I said at the I was very honest about it in my book to say that I did not want the onus of what I was trying to talk about to be on what happened or go by, or who did, what I did, what he did, what all of those things are not necessary. I think what was really necessary was, you know, the larger picture that I want you to actually say and normalize it and give women that agency to make the decisions, give them the you know, empower them with the kind of information that is needed to say, do you understand your basic rights? Do you understand what it means? Do you know, okay, if you want a divorce, and you don't have a support system, and you don't have help, and etc? What do you do after that, you know, who do you reach out to, you know, how do you even approach a lawyer? What happens after that, so I think I was very clear that the purpose of the book was much larger than just take the saying that it was something, you know, that I went through. So again, I think it was a very, one of those very conscious calls I took, right at the beginning to say, I don't, I'm not dwelling in the past. I'm not thinking of it, I think ever since I started this campaign, if I can call it and you know, ever since ever since I started talking about divorce and everything, I've always sort of spoken about it from a futuristic lens to say, this is where I want us to be this is this is the kind of support I want. And, you know, also sort of speaking to people to say, if your friend or cousin or aunt or whoever is going through this, and here's how you can be of support to them. Because sometimes, without even knowing it, we contribute to the stigma, you know, it could be a joke, it could be a comment, it could be talking about it with somebody else, you know, in the form of gossip, all of these things can be hurtful to the person. So I think those were my reasons to write this book. And I wanted to focus on those things. More than something, you know, that I went through. So I think because I was clear on those objectives, it became easier to say, these are my chapters, this is the content finish. So yeah, that's right.

Michelle D'costa 43:26

Yeah. No, that's, that's really interesting, because it makes me think of how you know, as humans, it's sort of this natural curiosity, that sort of we have like, as you said, you don't seem we immediately go to the school donate or widen it, this approach towards the story, right? We just wanted to share something. So I had a colleague who had gone through again, a painful divorce and and I remember she had not shared the story with anybody in the office. And when we got close, sort of, you know, when I understood, okay, this is, you know, the story and all of that. I remember people sort of, it's just so voyeuristic. When people literally approach me and they try to find out the story in very, very weird ways. Very indirect ways. And then obviously, but why does it matter? Right, like a whodunit or why doesn't it as you said, Does the it's more like, hey, but what do we do next? Right. And I remember when she had said that, you know, like, now looking forward at my life, I want to do my, you know, civil service exams, right? Like, I want to do my IAS exams. And, you know, people literally told her, but why would you do that? What's what's in it for your future? Why don't we just, you know, think about marriage because one one didn't work out. Think of one another. It is just it's sort of like I think you can easily get trapped into that circle. So it's very interesting that you mentioned yesterday that looking forward is

Shasvathi Siva 44:36

crazy, because, you know, back in 2019, when I started talking of MN, I actually said it out of the open that I went through, because I posted photos of my wedding sounds like if I posted photos on my wedding, I should be able to talk about the fact that I'm not married any longer, right? So when I posted that and then I started talking about it, you know, like the court experience, etc, etc. There was a day where I remember my girlfriends and I were sitting and we were looking at it. And they were like, Okay, let's Google and see what people are talking about. And when we just typed shots with the divorce, the third on that search was shot with the divorce reason. So, literally, they were searches and they were then they came across like Reddit threads, where people have tried to come up with reasons or like speculating, I'm like, why? What feels like, you know, I am such a, I'm a.in. This like, do you guys really have nothing else to do. But that is that is human nature, where we are really, we really want to know what happened. But I think I just held on to that to say, I don't want to like, it's just a choice that I'm making to say, I'm not interested in doing that, because I genuinely think because like I said, I'm so clear on the work that I want to do towards like normalizing divorce or you know, sort of erasing the stigma around it, I feel you don't need talking about the story then or even now, it just takes away from it. And then the focus becomes about like, exactly what you said about like, blame game. And like, all of those things. And I don't want that I don't want it snowballing into something. When it's a very personal matter to me, I'd rather focus on so many more important things and work to be done with this, you know, that this topic?

Michelle D'costa 46:22

Totally alone, I think I wouldn't have ever imagined that there would be a Reddit thread, which would want to find out a reason for that. But but you know, so for example, in Ayesha's book, also, you know, actually, you've covered so many incidents, you know, that have happened, this sort of ties up to the, to the sort of incident that I shared, you know, with my colleague, where this line in your book really stood out to me, where you say, there are two phases in your married life, right, where your husband's road desire for you existed, and on the other hand, his complete lack of desire. So this was an in this case, actually, this was something that sort of haunted my friend or my colleague for a long time, and I remember this line that has stayed where she said, Michelle, when I was sitting in the court opposite him, the only thing that I ever looked for in his eyes was like that desire that one word that I could hear from him that would say that, you know, Hey, it's okay, we're getting separated, but But you know, which shows that he has some sort of affection, and that sort of really broke my heart. So I wanted to know, you know, eyeshot of all the things that you've written, which incident or sort of which episode was really difficult to write about.

Aisha Sarwari 47:32

I think all of them were difficult, because each of them break your spirit in some way or the other. You know, the thing with traumatic brain injury is that the person who has it becomes, like an amygdala hijack, they think that somebody is attacking them, right in their own in their experience. It's, it's, it's like, you know, Saber toothed Tiger attacking, and so what do you do when that attack is happening? You lash out at everything around you. So in that reaction, because if my reality was that nothing was wrong, and there was no saber toothed Tiger attacking anyone, so the disproportionate Ness with the intensity that that my husband would turn on me on was such a shock, right from the start, even, you know, if it will be, there'll be a small flare up, and it would get out of hand really quickly, or it would be an insult on something that really mattered to me, you know, so So the so I think what happens is that the other person looks at you, not as a caregiver, and not as somebody who has paired with you to create a family and a structure but looks at you as the enemy. You know, and so I can see it in his eyes when he would have an episode. And a lot of these are epileptic related things. I mean, if anybody understands brain, neuroscience, they understand this, that you can have an epileptic fit, which is motor, which means your your physical muscles can have a spasm, or you can have a grand mal seizure or a petit seizure, but there's some seizures that are called focal seizures, which are happening in the brain, just like a seizure, but it's not presenting physically. And what that does is it makes your brain shift completely into perhaps a very, my mind, I'll be using the right word, but like, let's just say a very me centric, reptilian old brain, which is predatory, right. And so I'm using these words to give it a framework because I do feel terrible and I've talked about the shame of being on the receiving end of somebody who looks at you as a as a prey and they are a predator. What do they do with you honestly, which they bite you off and they chew you up and spit you out? So whatever that means, in terms of an intimate violence situation, that's what it means. Sometimes there will be things thrown or sometimes there will be insults for or sometimes they will just be gaslighting that this is not how What happened, or every one of those incidents were really hard. I don't think it ever stopped hurting. Even now, even now that I have written the book, even though that I have come out even now that I have control, even now that I got back my narrative and sort of defined my truth, because one of the things with a victim of intimate partner challenges or violence is that you use, you lose your sense of self, you, you lose your ability to understand if something isn't good event or a bad event, you lose your radar for feelings, and you become disassociated. But even now, after all this healing, I have that moment where you mentioned, your friend was sitting across her partner, and then just wanting him to like her. You know, and there's a lot of indignity in that. And there's a lot of maybe some Stockholm Syndrome vibe in there. And a lot of women who read my book get angry at me, you know, but I don't get angry at myself simply because I know that the path to healing is precisely to remove the shame from a very complex dynamic. Because, you know, it's very easy to do a commentary outside the dynamic, you know, as here is the right thing to do, you know, and you can also want it for me, I might want it for myself. But unless you are in that situation, right? Unless the bomb is going to go off in 30 seconds, and you have the choice to either stay or save someone, you don't know what you're going to do at that moment until you're actually in that situation, right? So there's one correct answer, but when you're in a situation, suddenly you realize that you need a little more mercy, you need a little more understanding. And I looked down on myself so much for, you know, being a caregiver of somebody who may not always recognize my contribution, and sometimes might even harm me. It made no sense. It made no sense from a survival perspective. But it did, it did make sense. If somehow, I use the radar of I wouldn't say love, but I would say a version of love, like, affection of love, or maybe a shadow of love, where, you know, maybe this could have happened to me. Right? And maybe I would have, you know, obviously, in the case that a woman is unwell, the man never sticks around, okay, like we're giving you talks three weeks, right, and you throw up on the side of the bed, you want to clean your own throw up, when you do survive two months later, you know, that's how it is. I know that it wouldn't happen the other way around. But still, I do feel that somehow, this is the spiritual part of our, and maybe the more feminine powers that we have. I do feel that until I can do it, I will do it. And until I cannot, I will not, which is why it's a very day to day process, you know, the journey is not over. The health is still really up and down. They're given Yasser, I think, five years, he's made it to seven, we don't know how long he will live. The book was not written for somebody who would have survived the book, you know, he's actually seen it in print, which is not how it was intended. So life is strange, and very paradoxical. And so I think the best feminine wisdom I have is to just lead with the heart. And someday, you know, maybe this will not work. But until that day, it's it's here, and I'm here because I want to be I don't know if that makes sense. Yeah, no, thank

Michelle D'costa 53:40

you so much for sharing. I think that's, that's, that's something that I've been thinking about as well. And especially, you know, I have two things to add here. One was, as you said, if you flip the coin, or if you flip the sides, you know, how often would a man bear all this and take care of a woman and this is something I had seen, you know, on Instagram, you know, like you, you know, sort of binge watching reels where when this woman had something unfortunate happened to her or an illness, I think she had a stroke and where she's completely sort of incapable of doing anything right now. And we just see her husband standing as a rock, taking care of her overwriting the past 10 years. And I usually have this habit of checking the comments for some reason. The first comment said that, you know, which man would I mean, it's rare, it's sort of seen as a woman would take it, but we would rarely see a man. So God bless this man. And I was just, it made me think a lot about this power dynamic. And another thing that you mentioned, Aisha, is that you know, this caretaker about, you know, the person you're taking care of, sort of not looking at you as sort of, you know, not being grateful, because obviously, they're not in that mind space. But looking at you as an enemy reminded me of this movie that I had seen called Little Fish. It's a recommendation. I don't know if y'all have seen it, where there's a sort of secondary in a dystopian world where there's a virus going around and you forget things and of course, it's because it plays with The mind, you know, sort of people, you know, they their personality changes, they forget, they get scared they are so not understanding why they are with the person who they are with and sort of, you know, treating them like a stranger. It's very interesting, which sort of approaches this, you know, dynamic between a couple, so I'm not gonna, I'm not gonna share much, but I think that's something that that sort of that movie made me think of us.

Tara Khandelwal 55:21

I think both these books really sort of, you know, made us think about so many things. No, I should say, in your book, you know, there are so many things that one was learning, you know, and one of the things that really shocked me that you know, how your name was sort of, like, automatically change your last name. And I was very shocked, because I'm not planning to change my last name at all. And, you know, I mean, this, this tiny, tiny things that like perpetrate the patriarchy. And all of the stories that you talk about, I think one thing that resonated with me was that how people just sort of, you know, because of these pressures are getting married, and we're always told, you know, as women that oh, your time is running out, you will not find anyone, the people that they know, then Oh, guys left, you know. And I think, honestly, Michelle and I were talking about it, and between the ages of 25 to 30, it's all you sort of hear about and even sort of like after that as well. And sometimes, you know, you're making decisions based on this imaginary husband that has or has not appeared. So I know, you know, people who may not have gone to graduate school at 26, because in a year, they'll have to get married, but your passes, and, you know, they're not found anyone and neither did they go to school, or neither? Neither did they sort of build their business or people who got married, you know, very early on because of this pressure, and then turns out that, you know, okay, this man who doesn't work at all, and, you know, you love to animate. So I think there's so much pressure on women especially, and even though sort of they're also working women and all of those things, but I think it hasn't yet left us. And so I think that these stories are so important, because hopefully, then the next generation, we're not going to be telling the next generation, oh, you need to get married or, you know, you're not going to find anyone and all these things and because it really percolate in your mind and, and then becomes something that you keep thinking about, I think all of us sort of have, you know, fallen victim to that as well. So I think I learned a lot through your book, but I want to ask you, what did you learn the most? Through writing about your book?

Shasvathi Siva 57:33

Yeah, okay. Um, I think I learned that we could write a book for free, I did not believe it at first, because it's such a big deal. And I was so intimidating at first to even think that oh, like, did I just sign on the dotted line at like, like this penguin on the letterhead. But I think that was my biggest learning to be very honest. But coming to the topic of, I think what I did, I spoke to about anything between 140 250 women, women, I would say like 90 95% of the interviews were women. So we had, like, long I had, you know, 45 minutes. So session one, our sessions of it all stem. I think what I really took out of that was just how resilient some people are just how, you know, some fights have been going on for years, and they still sort of found very similar to what Aisha was saying, and I'm not saying this in the divorce lens alone, but in the sense of exactly what she was also saying of what women go through, you know, especially in the time that you that we added. So I think I was just in awe of the kind of people I got to meet and how much I learned from them and to realize that you know, what, that there are so many times where the same people who I thought was wrong, felt really weak, and I think I got some sort of strength from people just opening up sharing their weakness sharing how like, even right now when Aisha said that, you know, it just shows how, you know, she, she, she said, colossally failed, you know, I took that word out, but there was so much strength in saying that it's so much of courage and you know, bravery to put it out there to actually wake up and say, Yes, this happened to me, but I am owning it, you know, I'm trying to see what I can do and get out of that. So I think we just learning we take a lot of strong women, I think made a big difference to the way I you know, I crafted my book after a point of time, you know, the fact that it got positive, you know, towards the end of it, etc. So, initially, for example, I had we started off thinking you know how I was going to In the book, but I just wanted to do like a crowdsourcing, I wanted to get more people's voices over there. So I think my biggest learning is that when women come together, we can do anything. And I have so much love, respect and admiration for the kind of stuff women have gone through and how they stand up for themselves, how they show up for themselves in their own ways. And I think it just takes so much courage to do that. So I think I'm so glad I got to do all those interviews, I got to talk to so many people, not all those stories made it to the book also, obviously, because, you know, there were like overlaps and whatever certain edits have been to be done. But, you know, there's no story that I heard that doesn't deserve to be like, told, you know, so, yeah, I absolutely enjoyed that process of talking to

Tara Khandelwal 1:00:57

other people. And I think one, I think there's so many nuances also admits that you debunk it, and you spoke about this earlier, also, that not all divorces have to, you know, I mean, divorces can be amicable, sometimes the relationship doesn't doesn't work out. And that's okay, as well. But there's still a lot of stigma about, you know, they didn't put in enough effort or this generation, they're giving up easily. You know, you'd rather sort of if things are not working out, then, you know, move ahead with your life. So you debunk a lot of those things as well. And one of the things I really liked I know, you know, the focus is on women, understandably so. But I really liked a lot of the stories, as you mentioned, one of the stories I found very interesting was about Nithin, who got divorced, and he has two children, and his wife got primary custody, and because of the juxtaposition, so you talk about how he had to move in alone, and men don't know. And you say, men don't know what it's like to be uprooted in the same way women do. And here's this guy for the first time, you know, kind of going through what as we went through all the time, and I really liked that juxtaposition, juxtaposed.

Shasvathi Siva 1:02:08

Very it was record turning point in the interviews that I was taking also, because you know, when he was telling me all of this is when I actually realized that, you know, what, we have all been uprooted at some point of time, from our parents, from our families, from whatever it is to say, the expectation is you get married, you go to your husband's house. I mean, how often is it that your husband actually moves out in so many cases, you just end up going into this new family and adjusting to like everything that they do. And it's not always that it's going to turn out to be good, right? It's actually very rare that it turns out to be to be really good and comfortable. So I don't think men ever understand it. And it's the same thing going back to that same even even if a man says yes, I understand it, or I will try to understand it until you are actually there. Until you You are the one who are getting uprooted, you are the one who's been taken away from your parents and told to live with a new family are new, everything is new, just the way every family functions. And let's face it, every family is dysfunctional. So you need to get used to you not pick yourself off from one form of dysfunction, throw yourself into another set of chaos and other things. So it's just so much that we do and men just don't. And when I spoke to this man, and you know, he was sort of taking me through that to say that I couldn't he couldn't sleep the first few nights because he was terrified of like, the scene. And he said, I've never felt that in my life. And I said, Yeah, because guess all men don't go through the shit. So I think that was, that was just very interesting for me to, you know, take. And he was also very cognizant of the fact that he has two daughters. So I think that sort of also gave him a very different perspective to say that, you know, okay, so now how am I going to raise them? That was, that's an interesting thing to take.

Michelle D'costa 1:04:04

In fact, this is because of this dynamic, right? And we know, we all we live in a patriarchal society, in fact, because the dynamic I think girls should be extra careful, you know, before they may decide to sort of get into any family because like, they say, you're not marrying the guy, you're marrying the family, especially in India, but I'm not saying that, you know, sometimes you do all the research, despite every everything, right? You have, like, you know, private investigators doing all the research and ever despite everything I'm saying things can go downhill, but actually, it's better, always better to, to sort of be prepared, especially because I think the adjustment that a woman makes is way more than what is expected of a guy and and when in fact, you know, we are seeing that a lot more women are writing, you know about this. So we have seen, you know, recent memoirs, you know, or even with auto fiction, like Mina, Candace Harvey's book when I hit you, sort of which is very interesting, you know, poetic, which talks about this really difficult marriage again, that was the love marriage, then you know, Do you see memos or divorce? Like, you know from they have Mehrotra, you know, where it's called How much is too much? You know, then there's even something called there's a book called rewriting my happily ever after by Ragini Rao, you know, so I want you to know for both of you so at the end, Aisha, because y'all are such advocates of, of, you know, women's rights, especially, you know, increasing awareness when it comes to divorce. In South Asia, which books have y'all come across that you all, like, you know, sort of about this topic? So it could be nonfiction, it could be fiction, do you have any recommendations, you know, books in India or Pakistan? You would love to hear?

Aisha Sarwari 1:05:35

Can I first started by a question about what we learned what I learned when I was reading? Because I think it's such a fantastic question. So I learned something that I think either Bell Hooks Who is it? Maya Angelou said about fighting back for women. I think she said one of them said that you cannot fight the oppressor using the tools of the oppressor. You have to change your tactics. And of course, this was said of slavery. But this is where intersectionality comes in. Because we are brown women, and we are oppressed. And we have class struggles, and we have ethnic struggles and other challenges as well. So we know this really well that, you know, there's so much power and there's so much abuse of power, and there's so much promise of violence at every step, that you have to be a special kind of stupid to kind of go fighting. Okay, and this is what people don't understand about our culture. Like, I remember I was on a bug book club and some angry woman asked me she like what is wrong with you? Why are you such a rural woman? You know, and, and I completely understood the anger. But also, I felt that it takes so much privilege to not understand that the prevalence of oppression is everywhere, it's in the legal system, it is in the fact that you have children that you're never going to get. And that's such a norm, it's in the fact that you're going to be shamed as a victim, all of those things that keep you silent, are not just one thing that you have to fight off, and there's nothing on the other end to catch you. So what a lot of people don't recognize is that do you want as a victim of something horrendous? Say you, you know, this is a new cause of divorce, something you've already experienced as, as violence, now you're going to go fight it. And there's going to be absolute isolation, even more isolation on the other side. So this is why, you know, there was a hashtag on Twitter called why I stayed and depicted some of these reasons, which are very rational, I feel, I really feel that when people are telling other women who don't have the same privilege privilege as them to fight back in the system, they should really like check to see if that's good advice, or not in the first place. And so what I learned was, I'm not going to win by fighting because I used to fight I used to have remember, I was educated in the US. I had a lot of vocabulary about, you know, feminism. And this was something that I always had, I had a bit of a rebel in me, but it wasn't working. Right. So what did work was this, again, not a gender related thing, but of a feminine power that requires you to let go, you know, and the moment I did that, you know, it was like, a bit like Taekwondo, we use your opponent's force against the opponent, rather than punching you just, you know, direct the anger, redirect the anger, or redirect the challenges, and let things that are breaking, breaking. So I found my courage and my salah for my freedom in the ability to let things break. I was so resourceful as a woman, that I would juggle a billion dollars, and I would let nothing break. But that was what was keeping a bad situation going, I was enabling a bad situation because I was just so ashamed that somebody would know that I am out of control. And by the way, in this book, the other thing I learned was that trauma can do such horrible things to you that you can be the aggressor. And I think that when I was putting Gasser on trial, I did not not put myself on that same trial, I did not not put my family on the same trials. So I just learned along the way that it's in the letting go. It's in the ability to take a hit. It's in the ability to recall and it's the ability of indignity and humiliation and pain where the healing starts, you know, and this is why I talked about all the terrible things I did. Sometimes I was horrible to your hair when he was sick. Even though that was a trauma response. It was horrible, and it was not a very good thing. But I talked about it so that it couldn't be weaponized against me because one of the biggest fears women have when they're trying to leave is you know they're going to get a lot of an evidence or a report card on what what a wrong woman they are, what a horror they are, what a black they are, what a bad cook they are or what a bad daughter in law they are. So in fear of that you just kind of like To protect yourself, but it isn't the divers that I allowed to, to ram into me where the bleeding stopped. Otherwise I would have completely flunked out long time ago. And as for I think your other question about book, it was obviously my favorite obsession is Margaret Atwood and her books are all on the same genre, which is, you know, women and fertility and how the patriarchy controls women's fertility. So The Handmaid's Tale is obviously a classic. And it looks like it's some utopian thing. But that's a lot of people, women's lives in the villages. They're just there to breed and produce heirs. And in my case, I had two daughters. So I didn't have anything going for me, I couldn't, like I tried to make the patriarchy work for me. But because I had nothing, you know, I had to I had to go the other route to survive. And I had to use what I had, which was storytelling, which was honesty, which was a bit of anger, and you know what to say about a woman draw wrath? Right. So I did allow myself and permit myself a lot of anger. And that is where the building up and the repair started.

Michelle D'costa 1:11:19

Yeah, just with the water. I don't know.

Shasvathi Siva 1:11:22

I think I wanted to mention, vena cava Samis book myself, and then you did it. So definitely, that was one of my other book that really, like sort of shook me up to say, you know, it's like, whoa, like, and of course, it's so wonderfully written it just like, you can't put it down despite feeling like, you know, disturbed by some of the things, but I think, I don't think I read a lot of books related to the topic, at that point of time, because I wanted to sort of have my own take on it, I didn't want to be I wanted to have my own opinions and sort of like, just put that out. So actually, on the contrary, what I read was all about love Bell Hooks. And I think, like I said, because I was holding on to that hope. And I really wanted to know what a healthy love boundaries, all of these things, I think sort of made me look at it very differently. It gave me very, very different understanding from the, you know, from saying that, okay, coming from toxic relationships, and, you know, talking to people who've been through so much, I think I took on a lot of like a sponge, like, you're not talking to 150 of this over a span of you know, writing this book was very difficult. For me, and also this, I'm still running my support groups, I'm still listening to those, you know, 15 stories every week. And so it was very emotionally heavy for me to do more reading or absorbing any more content or stories that were heartbreaking. So actually what I went for, even in terms of, you know, literally what I started watching, at that time, also was not anything to do with sadness, or heartbreak, or grief, or any of these things, I went the direction to say, give me hope, give me love, give me mindless, romcoms give me everything that sort of just, you know, fills me up with this. You know, like serendipity almost. So I think, I think it was almost a coping mechanism for me to say, I can't there's this, like, I'm exposing myself to this topic, and to these kinds of stories above and beyond what I can right now. So I needed to preserve a part of myself to get through, you know, listening to all of it. And at the same time, I was also trying to filter it to see, am I still keeping the book light because again, like I told you, that was an important part. For me to say, it has to be an easy read at the same time giving the information that I wanted. So while doing that everything that I had to like filter out from it was, you know, the rest of you was something I was taking in. So I think I needed a sort of karada that, you know, it's weird when I explain it. But you know, it's a process. That's all I can say.

Tara Khandelwal 1:14:10

Oh, that makes sense. Absolutely. And I think that the more you know, I think like we all been in toxic relationships, and like, not all of us, but a lot of us have been in toxic relationships. And I think what what helps like me personally, is that you know, these stories like sachet reading like Minakami Samis, all the stories that you know, your support group myself, once I've shared, you're able to recognize red flags, and you're able to recognize patterns, which you may not have otherwise and there are terms for it. So you learn like for example, you're on what is love bombing? Or you know, the whole pattern of like, what would be like to date somebody who's a narcissist. So then next time around when you're in the dating pool, or or whatever, you can identify it. And I think that's very important, actually, to be able to sort of, you know, have more of these stories out there. What I'm also really happy about is that the rom coms I love rom coms, as well as also showing now more and more green flags. They are showing characters who, you know, are not those like flashy sort of love bombing ties, but, but the underdog who's winning, you know, the goal of the romance, I think that's a, that's quite a nice shift, as well.

Shasvathi Siva 1:15:20